8055 MASH – (NORMASH)

(Norwegian Mobile Army Surgical Hospital)

Report by Eilif Ness, Corporal, Guard Squad Nov. 1952 – May 1953

“On June 25, 1950, seven divisions of North Korean troops crossed the border into South Korea, intending to conquer the entire South in three weeks. The South Korean Army was completely unprepared for the attack, and the only US force in Korea was a tiny advisory mission. The US government, under President Harry Truman – with the approval of the UN Security Council[1] – quickly decided to use US and UN forces to draw a line against the Communists in Korea, initially transferring forces from Japan.

Harry Truman downplayed the nature of the conflict because he was intent on limiting any sense of growing confrontation with the Soviet Union. Therefore, the conflict was not called a “war”, but “a United Nations police action« – a terminology that endured. The Korean War came to last three years, not three weeks, but it did not become a Great War, such as World War II, nor did it, like Vietnam a generation later, come to divide and haunt history.

More than half a century later, the Korean War remains The Forgotten War, outside the world’s general consciousness. Unlike Vietnam, the Korean War took place before television news came into its own. In the days of Korea, television news shows were short, bland, and of marginal influence – it was still largely a newspaper war in black and white.

Over the years, hundreds of movies were made about World War II – as late as 2001-2003 (major anniversaries of the Korean War) four major World War II films were made. Only four movies were ever made about the Korean War – two in 1951, one in 1956 and one in 1970. The three first were minor, forgotten movies; the last one became famous.

Robert Altman’s 1970 movie MASH, about a mobile surgical hospital during the Korean War, eventually led to a long running TV sitcom series that became very popular the world over. The sitcom did not in any way portray the terrible grisliness of that war; it did, however, create a niche for the Korean War in popular culture.

Thus, the true brutality of the Korean War never really penetrated the world’s consciousness. 34,000[2] UN troops died in it (28,000 of them Americans), and the South Korean Army lost 162,000 killed. The Chinese and North Korean losses were estimated at half a million.

The already considerable tension between the West and the Communist world grew even more serious when miscalculations brought China into the war. When finally an armed truce ensued, both sides claimed victory, although the dividing line was little different from the one that existed when the war began.

The Korean War had none of the glory of the recently concluded World War II – it was a grinding, limited war that nothing was going to come out of. After the Chinese entered the war in November 1950, the possibility of a large breakthrough never seemed near, much less anything approaching victory.

Soldiers returning from the Korean War found that their friends and neighbours were not really interested in what they had seen and done. The subject of the war was quickly dispensed with in conversation. So, the soldiers of Korea wound up with a kind of second-class status compared to that of the men who had fought in previous wars – a source of some bitterness.”

(Condensed from the Introduction chapter in the book “The Coldest Winter” by David Halberstam, 2008)

[1] The approval of the Security Council was due to the Soviet Union boycotting the Security Council meetings at the time (for other reasons), so they did not get to use their veto.

[2] Killed in action. In addition, 21,000 died of illnesses and accidents, to total 55,000 lives lost by UN forces.

The largest and bloodiest …

Out of UN’s many military missions[3] over the years, none has ever been so terribly bloody, with such enormous casualties, involving such large forces and so heavy weapons.

The UN effort in Korea involved nearly one million men: 9 divisions with personnel from 21 nations, who, together with 13 South Korean divisions fought against 1.2 million North Korean and Chinese forces for three years. Military losses: 34,600 UN troops killed in action, Republic of Korea Army: 162,400 killed in action (see Annex B for exact figures). The opposition’s losses are not known, but are estimated at more than half a million killed.

Recently (2013) South Korea hosted a reunion in memory of the signing of the armistice in July 1953. I was among the Norwegian veterans of the Korean War selected to participate in this reunion. It was a fabulous arrangement, held in Seoul and in Pusan, with more than 4000 veterans (all of them – necessarily – octogenarians!). However, all the speeches and the festivities left me with a distinct feeling of a need for a review and update of the Norwegian participation in the Korean War. This feeling was reinforced by the presence of the much younger Norwegian military who accompanied us on the vist – some of the with recent experience from Afghanistan – they deserve to be told about the real context of NORMASH.

Norway’s participation

The Norwegian contingent to the UN forces in Korea consisted of a”Mobile Army Surgical Hospital” – (MASH) – operating near the front line as component of the US 8th Army. It was operationally attached to US Army I. Corps (Bullseye) with the designation 8055 MASH (called NORMASH).

The unit was manned by 106 Norwegians (18 of which were women) under the command of a colonel (who also was NORMASH’ chief surgeon). The (all-Norwegian) medical staff numbered 58: 15 surgeons, 18 nurses and 25 assistant nurses. Support personnel (administration, communications, supply, transport, materiel, catering and security) numbered 48 Norwegians, reinforced with one platoon of ROK[4] Army military police. In addition, about 60 Korean civilians were recruited locally as support staff.

The Guard detail, responsible for camp security and perimeter defence, consisted of one squad (10 men) Norwegians (infantry) commanded by a First Sergeant, plus the Korean MP platoon (40). The latter manned six guard posts along the camp perimeter (listening posts at night) – a wide belt of barbed wire with trip flares. The Norwegians manned the main gate and patrolled the listening posts at night.

[3] Notably, the Korean War was a United Nations operation under the UN flag (see footnote no. 1 above), just as the later Suez action (1956) and the Congo intervention (1960). The later Vietnam War, however, was a US led operation without UN approval, as were the two Gulf Wars, the Afghan War and the Iraqi War. More about this on page 16.

[4] Republic of Korea Army

60 years later …

The reunion festivities in Seoul and Pusan in July 2013 were memorable events – four thousand surviving veterans from 21 nations met again.

Norwegian Korean War veterans visited Korean veterans and the Mayor of Uijongbu: Peder Fintland, Aage Kjeldsen, Gerd Semb, Arvid Fjære and Eilif Ness.

As the festivities went along, I gradually got the impression that the passing of time had created an image of the Norwegian role in Korea as a kind of humanitarian venture that had provided medical services to around 90.000 people. This is not a true picture, and obscures NORMASH’ true role.

The figure of 90.000 treated patients is essentially correct, but hides the fact that the Norwegian participation in the Korean War formed part of a large military operation and was an important contribution to the UN forces great effort in Korea.

There are several reasons for this gradual development. The primary reason, however, is very simple: By Present Day norms, most people – particularly in Norway – like to appear in the humanitarian role rather than in a military one – there is a marked reluctance to appear in any military role. Norway’s engagements in Bosnia, in Libya and in particular in Afghanistan have done little to change the political attitudes. However, Norway’s military of today has accumulated extensive know-how, and a high number of personnel with actual war experience – more that at any time since WW2

Several books and many articles have been published about NORMASH, but numbers and hard facts are few and far between. Actual figures are hard to find, as well as information about the various forces that participated and which we were part of. I feel that it is time to – once again – review (this time in closer dtail) NORMASH’ real role in the Korean War.

As all medical services – including those of the military – are humanitarian in nature, the Norwegian hospital contingency was of course a humanitarian contribution.

Military medical services, however, are just as essential to any military operation as are supply, transportation and communications. In addition to its primary task of abating the effects of personnel injuries, the qualities and mere presence of medical services are of great importance to the morale and combat efficiency of all units.

BLITZKRIEG

The Korean War started as a blitzkrieg. The North Korean Army’s massive attack across the 38th parallel overran the capital Seoul in only four days, and in less than four weeks swept South Korean and US forces all the way down to Pusan on the south-east coast. It was not until late July that large UN forces arrived in Korea.

On September 15th, the UN forces’ newly created Xth Corps (1st Marine Division og US 7th Infantry Division) made an amphibious attack at Inchon, just south of Seoul. They smashed through the North Korean forces, leaving a large part of it cut off in the south, and in a mere two months swept North Korea all the way to the Chinese border at Yalu River. This brought China into the war. A large scale Chinese Army counterattack forced UN forces back past the 38th parallel again, beyond Seoul. Then, during the spring of 1951 UN forces recaptured lost territory up to and just beyond the 38th parallel, where all had started.

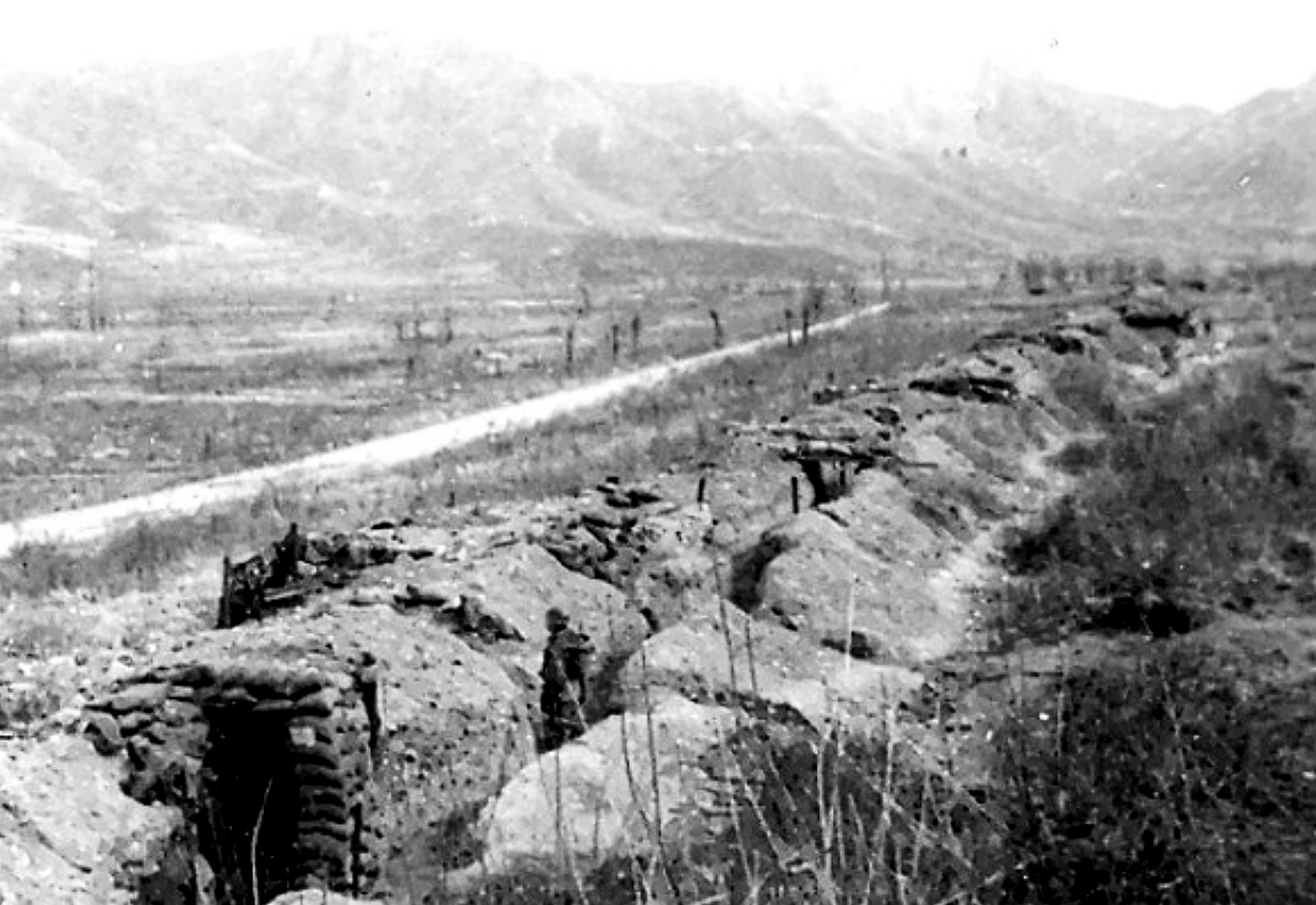

THE TRENCH WAR

This blitz-krieg phase lasted 11 months – the war razed Seoul four times. July 1951 the war changed character completely – it became a World War I-style static war of trenches and bunkers, dominated by artillery, mortars, night patrols and close quarters fighting. For the next two years, as armistice negotiations proceeded at a snail’s pace, intense and bitter fighting took place over insignificant patches of ground at a very high cost in human lives.

THE MASH CONCEPT

MASH stands for Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, a mobile surgical unit whose primary task is to follow combat units as close as possible, so that the seriously wounded receive surgical attention with the least possible delay. A MASH is (was) an operationally self-sufficient military unit with its own transport and supply services and its own defence.

The idea of providing advanced medical services as close as possible to the actual combat was launched towards the end of WW2 because so many of the seriously wounded died before reaching surgical treatment units. The idea was to counter this by having small mobile surgical units follow the combat units in the field to provide immediate surgery.

At the Normandy invasion, Auxiliary Surgical Groups (ASG) were introduced as forward units of the rear field hospitals. An ASG consisted of two surgeons, an anaesthetist, a nurse and two technicians, operating few kilometres behind the fighting. It paid off well: shorter transport and early surgical treatment dramatically reduced mortality among the wounded.

Immediately following WW2, the ASG concept was enlarged and renamed «Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals» with 60-bed capacity and a larger medical team, fully mobile with their own transport, and could be dismantled ready for transport in six hours, and reassembled in four hours after arrival. The idea was that there should be one MASH per division.

By June 25th 1950, when the Korean War hit a totally unprepared Western world as a bombshell, the MASH concept was untested and other US medical units in Japan had to equip and man three units at very short notice. These arrived in Korea in July-September. The first MASH unit in action was US 8209 MASH, which accompanied US 1st Cavalry Division on July 18th, closely followed by 8225 MASH being added to US 25th Infantry Division, which was already in place. US 8076 MASH followed on 25th July. These three MASH units served the entire UN operation throughout the 1950 campaign.

The rapid withdrawals and advances during the first 13 months – the movements spanned a war theatre extending nearly 1000 kilometres – created enormous transport problems, and the rear field hospitals (at Pusan) were unable to hang on to the advancing units. The MASH units became the only medical units in forward positions, and had to cope with sick and injured in addition to the battle wounded. In order to cope, the MASHs were enlarged, staff was increased and capacity enlarged to 200 beds. The idea of one MASH per division had to be abandoned – the result was one MASH per Corps, serving four divisions.

As the war changed from the fast-moving phase into a trench war, conditions were created which rendered the MASH concept most effective. They were placed as close to the front as possible, just out of enemy artillery range (at that time about 20 kilometres), which meant 10-15 km behind the trenches. By the time NORMASH arrived on the scene in July 1951 it was 60-bed unit with 83 staff, but by October it was increased to the new 200-bed standard with 106 staff.

THE NORWEGIAN CONTRIBUTION

It was the Norwegian Red Cross who initiated what became – in the end – a military field hospital, and they organised the first contingent sent to Korea. Only when the first hospital staff was relieved by contingent no. 2, (October ‘51) – was the responsibility transferred to the Norwegian Army medical branch (FSAN). However, the Norwegian Red Cross continued handling all personnel recruitment during the entire operation 1951-54.

As opposed to the Swedish and Danish contributions – the Swedish hospital in Pusan and the Danish hospital ship Jutlandia at Inchon – both operating far from the actual fighting – the Norwegian field hospital was a unit of the US 8th Army operating in the actual battle zone.

Commencing with contingent no. 2, all Norwegian personnel held US military ranks and wore US uniforms (with US 8th Army insignia), and, even if we were a non-combat unit, all non-medical personnel wore arms at all times.

The United Nations command was very pleased that Norway placed its contingent directly under the command of the US 8th Army. By carrying out its mission in the combat area proper the Norwegian contribution was placed in a class separate from the other contributors of medical support – the nearest comparable was the Indian 60th (Para) Field Ambulance that formed part of 1st Commonwealth Division.

NORMASH

By July 1951 the Norwegian field hospital finally set up its tents – one whole year after the start of the war (10 months after Sweden had set up its hospital in Pusan, and 5 months after the Danish hospital ship ”Jutlandia” anchored outside Pusan). In April, officers from the Norwegian Army medical branch had been in Japan and procured complete equipment for a 60-bed MASH from the US Army for delivery to Korea.

July 13th NORMASH went into active service at Uijongbu, about 20 km nord for Seoul and 16 km behind the front line, as part of US I Corps (Bullseye) as 8055 MASH, to serve the Corps‘ four infantry divisions (60.000 men). It was full speed from the first hour: During its first 40 days, NORMASH received 1048 patients – 23 of them Korean civilians.

During August and September UN advanced further northwards, and October 1st 1951, NORMASH moved 18 km. north to Tongduchon. It was at that point that staff was increased to 106. At the same time it was decided to extend Norway’s participation beyond the first six months, and to transfer the responsibility from the Norwegian Red Cross to the Norwegian Army Medical Service (FSAN).

In June 1952, NORMASH moved a further 3 km northwards, to Habongam-ri, 18 km. south west of the front line, where it was to remain for the rest of the war.

INTENSITY

1 Corps’ sector was the westernmost 40 kilometres of the front, from the Han River estuary to Chorwon. It was hotly contested because it blocked the main road to Seoul, only 40 kilometres to the south, which lead to heavy fighting about the strategic points T-bone Hill, Pork Chop Hill, Old Baldy, Little Gibraltar, The Hook and Nevada cities (map page 4).

These fights for the road to Seoul lasted over 20 months and produced a steady stream of wounded for NORMASH. The intensity of the fighting can be illustrated with figures: During the month of June 1953, UN forces fired 2.7 million rounds of artillery. That means 90.000 rounds per day – 63 rounds a minute around the clock. Enemy artillery added to this.

All the time, as long as we were there, artillery fire was a constant background day and night, the horizon an incessant sea of flames at night. After e few days one got used to it …

The Korean War makes the Gulf Wars and Afghanistan look like Lilliput wars. At July 27th 1953, UN forces counted 934.000 men against North Korea’s and China’s 1.2 million (see Annex B). Except for the Vietnam War (which was not a UN action) the number of casualties of the Korean War completely overshadows all other wars since World War 2.

The UN units lost 197.000 dead and missing (presumed dead) and 558.971 wounded. The number of wounded in the Korean War was the same as the total forces deployed (all branches) in Desert Storm (Iraq) in 1991 (550.000). In Korea, UN lost 54.000 in three years; in Iraq US losses were 5.000 over 8 years. More than two thirds of the UN losses were South Korean – the loss rates of the ROK-divisions were more than double those of the US divisions. The North Korean and Chinese losses were much higher.

The forward positions of the MASH units – close to the combat units – created a highly efficient medical and surgical service, which became even more effective as helicopters were put into use for evacuation of the wounded (even if road transport by ambulance continued to the primary means of evacuation) which saved thousands of lives.

GROUND BREAKING MEDICAL ADVANCES

New methods and means of wound treatment were developed, and the mortality rate among the wounded were halved in comparison to World War 2.(from over 4 % to 2.5 % in Korea), and new surgical methods and procedures reduced the amputation rate dramatically (from 36 % to 13 %). In addition, considerable reductions in the mortality rate from war related diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, hemorrhagic fever etc.

Thus, NORMASH personnel became part of ground breaking developments in emergency medical services. The large number of wounded during the Korean War, and the closeness to the scene of fighting, imparted a unique and comprehensive experience in both the treatment of war wounds and in handling large numbers of patients at short notice.

During the development of this report, I had long conversations with Lt. Col. Harald David Meum, who had extensive expeience from Norwegian participation in operations both in Bosnia and in Afghanistan – he informed me that many of the methods and techniques in use today, not only in a military context, but also by emergency services were developed in the heat of battle in Korea.

TRANSPORT OF THE WOUNDED – MEDEVAC

Road transport by ambulance dominated medevac (medical evacuation)– slow and bumpy even for the short hauls to the nearest MASH. The first two years of the war it was road transport only, even if the static war made for faster and better road transport. By 1952, however, as suitable helicopters became available, use of medevac by air gradually came into use.

Early in the Korean War, the H-5 Dragonfly was a widely used liaison helicopter. It was not an ambulance, but a system of two outboard stretchers with covers was developed and it saw limited ambulance use. 8076 MASH was the first to receive wounded by helicopter.

1952 saw the arrival of more than 100 of the helicopter type most used in Korea: the H-13G Sioux, a small three-seat bubble (later to be world famous through the TV series MASH).

The Sioux used one stretcher on each skid, sometimes with a cover, sometimes with just with tied-down blankets – primitive but effective.The versatility of the Sioux – it could land almost anywhere – led to its extensive use for medevac, even if the patients were exposed, limiting it to relatively short flights. .

Finally, in 1953 a considerably larger helicopter came into service: the H-19 Chickasaw, which allowed for medical treatment of the wounded during flight. In ambulance version the Chickasaw could accommodate 8 stretchers and allowed in-flight treatment of patients, a tremendous improvement in medevac.

THE PATIENTS

The losses of the nine UN divisions (apart from ROK losses) during the static war alone (June ’51 – July ‘53) were about 13.000 killed and 50.000 wounded (KIA and WIA only). NORMASH’ mission was to serve the four infantry divisions (60.000 men) that made up I. Corps of the US 8th Army.

At any given time it took 18.000 men to man the 40 km. of trenches that made up I. Corps’ sector of the front, and their activities (mostly night-time patrols) and the artillery and mortar duels resulted in a daily average of 3 killed and 14 wounded plus 3 other injuries (varying greatly from day to day, peaking at 64 surgery patients in 24 hours on July 1st, 1953).

During NORMASH’ first 737 days –while there was a full scale war going on – we were a military surgical hospital, treating just under 20.000 patients. 12.271 of them were hospitalised (62%), the remaining 7.500 were ”outpatients”, mostly Korean civilians (some of them war wounded). 10.488 of those hospitalised (86%) were sent on to rear hospitals, while 1.706 patients (14%) were released and returned to unit.

During active war, the capacity for treating civilian patients at an active MASH was of course very limited. As combat wounded had priority over all else, civilian patients could not be allowed to reduce capacity. Due to the medical needs of the (limited) local population in the immediate camp area (Tongduchon village), NORMASH’ commanding officer raised this question with the US 8th Army HQ several times; the end result, however, was that the number of civilian day patients at NORMASH (based on my own observations) averaged less than 10 per day up to the armistice (See Table II, and Annex A).

NORMASH’ MILITARY EFFORT

In order to determine NORMASH’ purely military role, one must dig deep. By analysing the available data, combining several sources, adding one’s own experience and some qualified guessing, it is possible to produce a fairly informative picture. The figures become particularly interesting when divided between active war service and post-hostility activities, i.e before and after the armistice July 27th, 1953.

”More than 90.000 patients” is a statement that appears repeatedly in most descriptions of NORMASH. The prominence of this impressive figure is understandable, but has little to do with NORMASH’ real mission. Analyses of the detailed patient statistics show that 8,000 were dental patients, that 70.000 of them were treated after termination of hostilities (July 27th 1953), that 56,000 of them were Korean civilians, and that 95 % of these were ”outpatients” (treatment without hospitalisation)

Subsequent to the armistice becoming effective July 27th, 1953, NORMASH gradually changed character. During the following 448 days – until October 18th, 1954 – NORMASH treated three quarters of the much publicised 90.000 patients, two thirds of them Korean civilians – practically all of them ”outpatients”. Only 5 % (2.554) were hospitalised.

Lowered military readiness requirements led to considerably extended average hospitalisation times to an average of 14.5 days per patient, as opposed to the 3-day limit of the MASH-concept. Very few patients were sent on to other hospitals.

NORMASH became an ordinary hospital: military personnel made up only 31 % of the patients.

COMBAT WOUNDS

5.326 combat wounded were received during the active hostilities period. These made up 55% of all hospitalised patients; a similar number were admitted for other reasons: 20% were identified as ”other injuries” (traffic accidents, work accidents, frostbite, fractures, accidental gunshots, violence etc.), while 25% were identified as ”illnesses”. Most of the illnesses were typically war related, as mentioned above.

”Other injuries” and ”illnesses” made up about 45 % of all those hospitalised before the ceasefire. After the ceasefire, all the hospitalised belonged to this two patient categories. These figures are consistent with official US Army records, which show that 38% of the Korean War losses were not combat related (KIA+ MIA = 33.629); total losses: 54.246.

WHO WERE THE PATIENTS?

A breakdown by nationality shows that patients representing 15 different nations (plus some POWs from North Korea og China) landed on NORMASH’ operating tables, which means nearly all of the participating nations were represented. How could this be, when NORMASH covered less than 25 % of the front line? The explanation lies in the way UN forces were organised.

The core of the UN forces was the 8 divisions of USA plus the Commonwealth Division, and ROKs 12 divisions (about 300.000 men).

These 21 divisions made up five Corps, each of 4 or 5 divisions, covering the 165 kilometre front as follows (West to East): US I.Corps, US IX.Corps, ROK II.Corps, US X.Corps, ROK I.Corps.

All combat units sent by UN member countries were seconded to US divisions – except the ground forces from the nations of the British Commonwealth, who combined to constitute the 1st Commonwealth Infantry Division.

NORMASH served I. Corps’ sector – the western part of the front, from the Han River estuary to just west of Chorwon, about 40 kilometres of frontline. Each Corps would change its component units as divisions were moved about; two divisions, however, were part of I. Corps throughout: Commonwealth Division and ROK 1st Division.

Table I: Secondment of non-US UN contingents to US Army unit (numbers as of July 1953):

| Non-US UN contingents seconded to US and Commonwealth Divisions | |||

| Country | Contingent (type of unit) | Personnel | Seconded to |

| UK | 2 Inf. brigades +1 tank battalion | 14.198 | 1st Commonw. Inf. Division |

| Canada | 1 Infantry brigade | 6.146 | 1st Commonw. Inf. Division |

| Australia | 1 Infantry regiment (2 battalions) | 2.282 | 1st Commonw. Inf. Division |

| New Zealand | 1 Artillery battallion | 1.385 | 1st Commonw. Inf. Division |

| India | 1 Field ambulance | 90 | 1st Commonw. Inf. Division |

| Turkey | 1 Infantry brigade | 5.453 | US 2nd Infantry Division . |

| France | 1 Infantry battalion | 1.119 | US 2nd Infantry Division |

| Netherland | 1 Infantry battalion | 819 | US 2nd Infantry Division |

| Ethiopia | 1 Infantry battalion | 1.271 | US 7th Infantry Division |

| Colombia | 1 Infantry battalion | 1.068 | US 7th Infantry Division |

| Thailand | 1 Infantrt regim. (3 battalions) | 2.120 | US 25th Infantry Division |

| Belgium | 1 Infantry battalion | 900 | US 3rd Infantry Division |

| Luxembourg | 1 Infantry platoon | 44 | Part of the Belgian battalion |

| Philippines | 1 Infantry battalion w/artillery | 1.496 | US 3rd & 45th Infantry Division |

| Greece | 1 Infantry battalion | 1.263 | US 1st Cavalry Division |

| Norway | 1 MASH | 106 | US I. Corps |

| 39.654 | |||

Altogether, six other divisions were part of US I. Corps for shorter periods: US 1st Cavalry (1951), US 25th (1951), 1st US Marine Div (1952-53), US 45th (1951-52), US 2nd (1952), US 3rd (1952), US 7th (1953), and US 25th again (1953). Only two US-divisions never formed part of I. Corps during the war : US 24th and US 40th Infantry Div. ROK 9th Div a short time in 1952 – the remaining 10 ROK-divisions all formed part of the other four Corps.

Thus, almost all the UN contingents seconded to the US divisions served in the I. Corps sector at one time or another, so their wounded, injured or ill wound up at NORMASH, which explains why the patients represented so many nations.

At the most intensive periods of fighting in the I. Corps sector during the static war – November/December 1952 – the battles for Pork Chop Hill and The Hook – and March 1953, the Pork Chop-Old Baldy and Reno-Carson-Vegas battles, both 2nd Div, 25th Div, 7th Div and Commonwealth Div were involved, and thus Australians, Brits, Canadians, Colombians, Ethiopians, French, Dutch, Thais and Turks.

Totals for the whole war for the same nine divisions (KIA and WIA only, apart from ROK) were 27.619 killed og 103.257 wounded (ROK losses were much higher than for UN units – most data indicate percentages three times higher).

Table II: In-patients at NORMASH 13. July 1951 – 27. July 1953 (737 days)

| NORMASH-patients by nationality og unit | ||

| Nationality | Division | Number |

| USA | 1Marine,1Cavalry, 2 ,3, 7, 25, 45th Infantry Divisions | 5,259 |

| ROK Army (South Korea) | 1, 2, 9th Infantry Divisions | 2,082 |

| UK | 1st Commonwealth Division | 2,059 |

| Canada | 1st Commonwealth Division | 1,241 |

| Australia | 1st Commonwealth Division | 447 |

| Belgium & Luxembourg | US 3rd Infantry Division | 130 |

| North Korea/China | Wounded prisoners of war | 172 |

| Ethiopia | US 7th Infantry Division | 68 |

| Greece | US 3rd Infantry Division | 62 |

| Colombia | US 7th Infantry Division | 53 |

| Thailand | US 45th Infantry Division | 50 |

| France | US 2nd Infantry Division | 39 |

| Turkey | US 25th Infantry Division | 28 |

| Netherland | US 2nd Infantry Division | 28 |

| Philippines | US 3rd & 45th Infantry Division | 21 |

| India | 1st Commonwealth Division | 3 |

| Uknown nationality | 24 | |

| China (UN soldier) | 1 | |

| Sweden | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 11,768 | |

| South Korean civilians | 2,720 | |

| Norway | 50 | |

Besides I. Corps’ ROK-divisions (1st and 9th), IX. Corps had two ROK-divisions (2nd og 9th); X. Corps also had two (12th and 20th) while ROK I. Corps and ROK II. Corps were ROK only (with ROK divisions 6th, 7th, 8th, 11th, 15th, 21st and Capital Division).

In addition to the regular military forces, there was the Korean Service Corps – more than 50.000 strong – unarmed and on foot, who served the entire front line as porters. They were the ones who carried all supplies on their backs from where the trucks stopped, up the hills, into the trenches – ammunition, food, and all other kinds of stuff up, an d the dead and the wounded down. Their losses are not recorded anywhere.

Korean War Timeline during the 4th NORMASH contingent, October 1952 – May 1953:

- Oct. 14-25 1952: The battle for Hill 598 (Sniper Ridge). US 7th Infantry Division defended Kumhwa againstkChnese attacks (the Iron Triangle).

- Oct. 26-28, 1952: Battle of the Hook (Commonwealth Division).

- Nov. 3, 1952: Chnese attack on Hill 851 (Heartbreak Ridge) held by 2nd Battalion, 160th Infantry Regiment (US 40th Infantry Division)

- Dec. 25, 1952: Chinese attack on T-Bone Hill. 38th Infantry Regiment (US 2nd Infantry Division) repulsed the Chinese after hard fighting.

- Jan. 25, 1953: US 7th Infantry Divisions 31st Infantry Regiment attacked Spud Hill.

- March 17, 1953: Massive Chinese attack on Hill 355 (Little Gibraltar),which was held by 9th Infantry Regiment (US 2nd Infantry Division).

- March 23-24, 1953: Chinese attack on Old Baldy/Pork Chop Hill defended by 31st Infantry Regiment (US 7th Infantry Division). Old Baldy was lost (defended by the Colombian battalion) but became no man’s land.

- March 26-30, 1953: Massive attacks on outposts Nevada cities (Vegas-Reno-Carson), defended by the 5th Marine Regiment – one Chinese regiment was annihilated.

- April 16-18, 1953:Last battle of Pork Chop Hill. 17th and 31st Infantry Regiments (US 7th Infantry Division) suffered heavy losses, but Pork Chop Hill was held.

DAILY LIFE AT NORMASH

As described above, the guard squad of 10, with 40 Korean military police, were responsible for guarding and defending the hospital camp. Many of the MPs were North Koreans who had enlisted in the ROK Army. The hospital camp was in a zone 20 km deep behind the actual front line.

This zone was used by units temporarily in reserve positions, and by many Corps level support units. There were very few civilians in this area, and therefore few communist guerrillas (North Korean troops cut off by the Inchon landing, blending into the local population) which were a real problem further south.

Our perimeter defence consisted of a wide field of barbed wire with numerous trip-flares surrounding the camp. Six guard posts (listening posts at night) were manned by Korean MPs. One Norwegian patrolled the listening posts at night. Our main contact with the war, apart from supervising the ambulance and supply traffic through the main gate, was the incessant thunder of artillery fire.

The TV-series MASH gave a perfect picture of NORMASH: the tents, the mud, the equipment and the atmosphere (excepting Hotlips), even if it falsely leaves the impression that helicopter was the primary transport for the wounded (90 % of all wounded came by road in ambulances), and also features convalescents. There are no convalescents in a MASH – all patients are shipped to the rear within 72 hours after treatment.

The Norwegians who competed for the hotly contested positions at NORMASH: could be divided roughly into three categories by motivation: 1) Idealists eager to save lives, 2) the adventurous, and 3) those with military background who wanted war experience on their records.

The first category quickly engaged in off-duty activities like running a health policlinic for the few civilians still in the area, and became dedicated to that. The other two groups found their way to groups of their own kind among other UN units in the area, and visited the front as often as they got the chance.

Guard duty was not strenuous, but terribly monotonous: The routine was two hours guard duty/six hours off for nine days, the tenth day was off duty for 24 hours midnight to midnight. The monotony was broken each time heavy fighting broke out at the front in our sector (such as when Old Baldy changed hands twice in two days) – that was always followed by a rush of wounded, overfilling pre-op, and every hand available was called on to empty the ambulances and move the wounded around.

The bright side of life was he Sergeant’s Club – every night the NCO mess tent was turned into a bar, open 1800 to midnight, with very reasonably priced drinks (money was Scrips only – US military money). Personnel carrying weapons were not served, and as all non-medical personnel carried arms at all times, a table was set up in a corner of the tent for them to leave their weapons.

The Club was open to all UN personnel, including those from units camped in the neighborhood. As the word spread around, interpretation of ”neighborhood” became quite liberal, and produced visitors from all kinds of surrounding units, giving us an insight into the enormous machinery that constitutes a modern army – all kinds of specialist units: water supply, solid waste, road repair, vehicle recovery, mail etc., even corpse identification units.

About every six weeks, Ist. Corps front line units switched into standby positions behind the front line proper. They quickly found out about NORMASH’ Club and were allowed in as guests of one of the guards. A couple of times when one of 1st US Marine Division’s battalions camped in the vicinity, their bad manners led to incidents requiring us to close the gates, which created stress – and sometimes gunfire.

Because the Commonwealth Division was part of I. Corps and thus in the sector we served, Australians and Brits were frequent guests: 1st Battalion Royal Australian Regiment og 1st Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, which resulted in frequent contact between their personnel and us Norwegians – a reciprocal affinity that is a well known phenomenon.

These visits went both ways, and opened up an almost fee access for us to the front line in the Commonwealth Division sector, including the forward outposts. This we used on our days off – we hitchhiked up to the front to visit our fiends there.

Final Remark: Norwegian personnel made a great effort for civilian Koreans, but that should not be allowed to overshadow the fact that that Norway’s participation in the Korean War was a MILITARY effort. A large majority of the hospital’s activities after the armistice of July1953 was treatment of civilian patients.

Should any doubt remain as to the nature of NORMASH’ role in the Korean War, it should be removed permanently by the text that accompanied the United States’ unit decoration The Meritorious Unit Commendation which was awarded to NORMASH twice: For the period July 1951 to Jul 1952 and again for the period July 1952 to July 1953:

“The Meritorious Unit Commendation is awarded by the United States to military units for exceptionally meritorious conduct in performance of outstanding services for at least six continuous months during military operations against an armed enemy. The services must be directly related to the combat effort.”

In addition, NORMASH was awarded The Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation. This decoration is issued by the government of South Korea to both Korean and foreign military units “for exceptionally outstanding performance of duty in action against an armed enemy.“

The Big Cheat: The 1988 Nobel Peace Prize

When industrial magnate Alfred Nobel instituted his series of prizes (administered by the Swedish Academy) he separated out the Peace Prize, and entrusted its administration to Norway’s parliament, the Storting. The Storting appoints the five member of the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committe, usually three previous politicians and two cultural personalities.

In 1988, the Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee decided to award its prize for 1988 to “the United Nations Peacekeeping Forces”, a decision that was widely applauded, at least until the fine print became apparent with the text of the award speech, which had been carefully worded to exclude UN action in Korea in 1950-53:

“The original United Nations treaty does mention the possibility of military involvement on the part of the United Nations in the event of hostilities, but, because of the relationship between the great powers, it has never been possible to make use of this part of the treaty – the possible exception being the action in Korea in 1950.

… peace keeping operations were commenced in 1956 (…) in connection with the Suez crisis. The Security Council was unable to act because of a veto from two of the member states. This was solved by summoning the UN General Assembly to a special session, which passed the «Uniting for Peace» resolution that gives the United Nations’ General Assembly the power to intervene in the event of the Security Council being unable to act. This resolution was used to deploy a peacekeeping force …”

The “possible exception” referred to happens to be the only time that UN Security Council – UN’s highest operational authority – actually did approve a military action as the Treaty permitted. It so happened that “the relationship between the great powers” at the time prevented a Soviet veto (see footnote 1, page 2).

So, in 1988, the Nobel Committee chose, as the starting point for “UN Peacekeeping Forces”, a clever paper manoeuvre that permitted the bypassing of the Security Council in 1956, rather than the legal, straightforward decision of 1950. That way, they managed to exclude a previous legal UN action that cost 34,000 (non-Korean) UN forces’ lives. Which proves that today, most people (particularly politicians) like to appear in a humanitarian role rather than in a military one.

How did I get into this war?

On the 25th of June 1950 I had just signed on the Norwegian merchant ship M/S ”Høegh Silverbeam” in Australia, when the news came over the ship’s radio: North Korea had launched a full scale attack on South Korea. I was 19, only five years had passed since World War 2 – World War 3 seemed to be just around the corner. Little did I realise at that moment that just two years hence, I would be in the middle of the Korean War.

Before that, however, I visied Italy and Spain for a year, then I did my national service in the Engineer Regiment, serving in the Norwegian 521 Brigade in Schleswig-Holstein, part of the British Army of the Rhine in occupied Germany. When that service neared its end in the autumn of 1952, a circular arrived, offering enlistment for service with the Norwegian field hospital in Korea.

It was well paid: 6000 kroner guaranteed in the bank for 6 months of service – nearly a year’s wages at that time – here was a potential study financing. The competition was stiff – nearly 1000 applicants fought for 106 positions. The recommendation from my CO in Germany, experience from working abroad and language qualifications got me in.

A lifetime later, I see clearly that my half-year in Korea shaped me in more senses than one. It is impossible to imagine what war really is – unless you have been in it yourself. No movie, no TV can impart that experience. You must be there, inside it. Reality etches it into your memory.

When you are in the middle of it, it hits you in the gut – it is war: guns roar, people die, there is no way out. You are a tiny, tiny wheel in a gigantic machine: An army on war footing, with death and destruction as it purpose, with its own rules and laws.

Only the incredible adaptability of the human mind makes it possible to remain sane. Once you do get out, the experience remains with you forever.

ANNEX A

Note on the organisation of US Army units in 1952.

For the guidance of those who are not familiar with military organisation models of 60 years ago, I add the following informative note:

The size and composition of the various ground forces of the US 8th Army in Korea largely followed the lines of World War 2. Units at each level normally comprised 3 identical elements (subunits) plus staff personnel and/or support unit(s). Basically, infantry units were composed as follows (personnel numbers are approximate):

- Squad: 8 riflemen plus one machinegun (2 men): Total 10.

- Platoon: 3 rifle squads plus staff (8): Total 38.

- Company:3 rifle platoons plus staff/support (30): Total 150.

- Battalion: 3 rifle companies plus one weapons company (130) plus support company plus staff (120): Total 700.

- Regiment: 3 battalions plus one support battalion (600) plus staff (300): Total 3,000.

- Division: 3 infantry regiments plus one artillery regiment (2000), one engineer regiment (2000), one signals regiment (1500). one transport regiment (2500), medical staff (500), plus division staff (200): Total 18,000.

The infantry Squad is the smallest unit of infantry, commanded by a corporal or a sergeant. Named numerically (1st squad, 2nd squad, 3rd squad)

An infantry Platoon of three rifle squads plus staff is commanded by a lieutenant with a 2nd lieutenant as 2iC. Named numerically (1st platoon, 2nd platoon etc.)

An infantry Company of three rifle platoons plus a weapons platoon (mortars, medium machine guns and light anti-tank weapons) plus staff is commanded by a Captain with 1st lieutenant as 2iC. Named alphabetically (A company, B company, etc).

An infantry Battalion of three rifle companies plus one heavy weapons company (D-) with heavy mortars, recoilless guns, heavy machine guns, anti-tank guns plus one support company (E-) of engineers, signals, medics and transport, plus staff, is commanded by a Lt. colonel with a Major as 2iC. Battalions are numbered numerically 1stBn, 2nd Bn, 3rd Bn.

The next larger unit might be one of two types:

1) A Regiment of 3 battalions plus additional regiment-level units of engineers, armour (tanks), artillery, signals and division staff commended by a Colonel. Three regiments would form a Division commanded by a Major General (total 18,000-20,000) .

2) A Brigade of 3 battalions with additional company- or battalion-size units of engineers, armour (tanks), artillery and signals (sometimes called Regimental Combat Teams – RCT) commanded by a Colonel, comprising 4,000 – 5,000 men. Three such Brigades would form a Division (total 12,000-15,000).

The difference between a Division with a Regiment structure and one with a Brigade structure is that a Division of Regiments would operate only as a complete Division, while Divisions of Brigades would be able to let their component Brigades (or RCTs) operate as independent units. In the Korean War the Regimental system was predominant.

In very large theatres of war, such as World War 2 (and the Korean War) most armed forces subordinate their Divisions to one further level: Corps (numbered by Roman numerals (I, II, III)

Each Corps would comprise three to five Divisions, their role being to provide support at levels above and beyond the Division-level capabilities, such as heavy artillery, anti-aircraft defences, logistics, transport systems, medical services (the MASH were typical Corps-level support – one MASH for each Corps).

Corps also provide other advanced heavy support, such as running civil utilities like water supply, waste management, electric power, railway systems, maintaining roads and bridges, communications (telephone systems and public broadcasting) etc., as well as organising the supply needs of its component divisions.

Three Corps plus additional administrative and command units would form an Army.

The UN side of the Korean War was organised with five Corps. The composition of each Corps varied over time as divisions were rotated and exchanged, and some Corps comprised both US and ROK divisions. At the time of the armistice (July 1953), the five Corps of the UN army were composed as follows:

- I Corps (US): 1st US Marine Div., Commonwealth Div., 7th US Div., ROK 1st and ROK 9th Div. (5 divisions)

- IX Corps (US): 25th US Div., ROK 2nd, ROK 7th Div.(3 Divisions)

- X Corps (US): 40th US Div, 45th US Div, ROK 12th Div, ROK 20th (4 Divisions)

- ROK I Corps: ROK 6th Div, 8th Div and 11th (3 Divisions)

- ROK II Corps: ROK 15th Div, 21st and Capital Div. (3 Divisions)

The three US Corps constituted the US 8th Army.

The two ROK Corps constituted the ROK Army.

ANNEX B

NORMASH PATIENT DATA

| Total | Before the armistice | After the armistice | ||

| All patients | 90,000* | 27,201 | 62,799 | *Undocumented |

| Dental patients | 8,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | Estimated |

| All patients ex dental. | 82,000 | 19,701 | 62,299 | Calculated |

| Military patients | 26,030 | 12,201 | 13,829 | Calculated |

| Civilian patients | 55,970 | 7,500* | 48,470 | * Estimated |

| Hospitalised | 14,755* | 12,201 | 2,554 | *Documented |

| Combat wounds | 5,326* | 5,326 | 0 | * Documented |

| Other injuries | 4,086* | 2,492 | 1,594 | * Documented |

| Diseases | 4,998* | 3,048 | 1,950 | * Documented |

| Died at the MASH | 150* | 150 | 0 | * Documented |

| Released for service | 4,314* | 1,760 | 2,554 | * Documented |

| Transferred to other hospitals | 10,488* | 10,488 | 0 | * Documented |

| Unregistered* | 345* | 0 | 345 | * Documented |

| Days in action | 1,185 | 737 | 448 | Calculated |

| Mil. patients per day | 22 | 17 | 31 | Calculated |

| Civ.patients per day | 47 | 10 | 108 | Calculated |

| 69 | 27 | 139 | Calculated | |

| Hospitalised, % | 18.0% | 61.9% | 4.1% | Calculated |

| Hospital days* | 73,637* | 36,603* | 37,034* | * Documented |

| Hospital days per patient | 5.0 | 3.0 | 14.5 | Calculated |

| Documented data are from dr. Bernh. Paus’ report, FSAN 1955. Undocumented figures are estimates and calculations by the author of this report | ||||

ANNEX C

UNITED NATIONS FORCES IN KOREA as of 27 July 1953

| Number of troops: | |||||

| Country: | KIA | MIA | WIA | POW | |

| Republic of Korea | 590,911 | 137,899 | 24,495 | 450,742 | 8,343 |

| United States | 302,483 | 23,715 | 4,820 | 92,134 | 7,245 |

| Commonwealth | 24,101 | 1,964 | n.a. | 4,972 | n.a. |

| – UK | 14,198 | 1,078 | n.a. | 2,692 | n.a. |

| – Canada | 6,146 | 516 | n.a. | 1,042 | 7 |

| – Australia | 2,282 | 339 | n.a. | 1,160 | n.a. |

| – New Zealand | 1,385 | 31 | n.a. | 78 | n.a. |

| – India | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n.a. |

| Turkey | 5,453 | 721 | 168 | 2,111 | n.a. |

| Thailand | 2,120 | 136 | 0 | 469 | 0 |

| Philippines | 1,496 | 92 | 0 | 356 | 0 |

| Ethiopia | 1,271 | 122 | 0 | 566 | 0 |

| Greece | 1,263 | 194 | 0 | 459 | 0 |

| France | 1,119 | 287 | 7 | 1,350 | 12 |

| Colombia | 1,068 | 146 | 69 | 448 | 0 |

| Belgium | 900 | 97 | 0 | 355 | 0 |

| Luxembourg | 44 | 7 | 0 | 21 | 0 |

| South Africa | 826 | 20 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 819 | 116 | 3 | n.a. | 1 |

| Norway | 106 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Denmark | 150 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sweden | 174 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Italy | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total troops | 934,354 | 167,480 | 29,562 | 558,971 | 15,608 |

| Total killed | 197,042 | KIA: Killed in action | |||

| MIA: Missing in action | |||||

| WIA: Wounded in action | |||||

| POW: Prisoners of War | |||||

| n.a. : Data not available | |||||