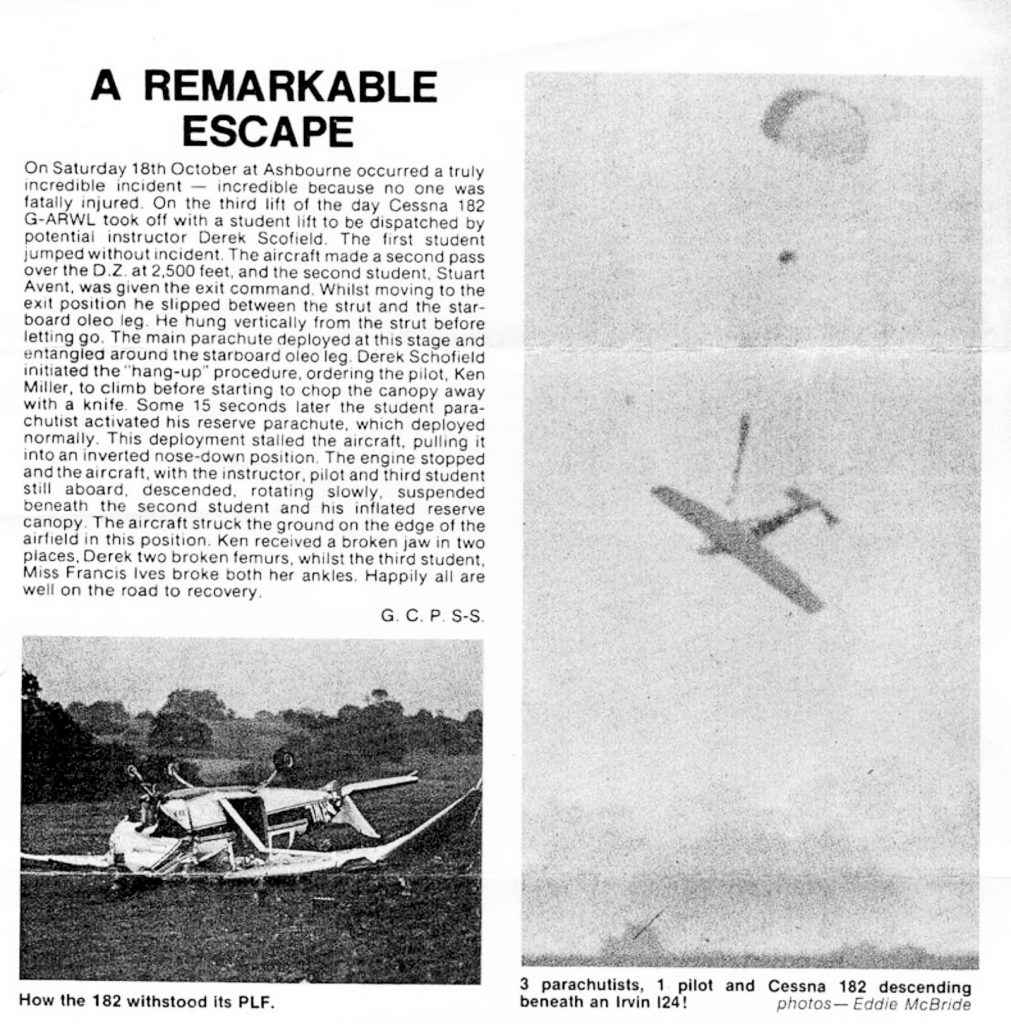

(This story became an international media sensation that, at the time, was spread all over the world as a curiosity news item. 15 years later (1994) the Norwegian TV channel TV3 re-enacted the incident with flying, jumping and interviews, in a program called «Alarmen går»).

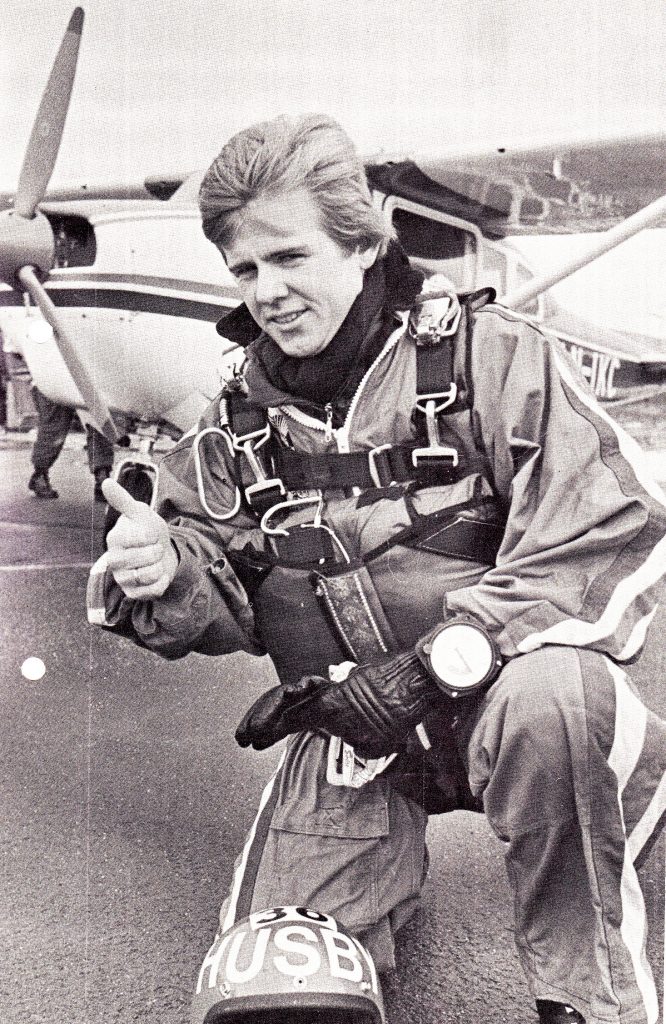

A large part of my life I have been actively engaged in skydiving – throughout the 70’ies I was very active. I also acquired a pilot’s licence (PPL) – someone had to fly us to exit altitude. We created the ”Nimbus” Skydiving Club at Rygge Air Force Base (RNoAF) just south east of Oslo, and after a few years, the club had acquired two jump aircraft: One Cessna 182 (LN-TSB) and one Cessna 206 (LN-IKC).

Sunday December 11th, 1977:

Nimbus scheduled training jumps every weekend before Christmas, despite the cold and the short days. This Sunday it was about 5 degrees below zero (C), a light but ice cold southerly breeze and overcast at 5000 feet. During the night there had been a light snowfall, less than two inches. The students from our latest training course lined up at Rygge AFB at 1300 hrs (i.e. after church hours, it being a Sunday).

Usually I jumped myself, but this particular day it was my turn to fly the jump aircraft – Nimbus’ aircraft number 2, Cessna 206 LN-IKC. The low ceiling dictated student training only, and as load number four I got jumpmaster Arne Husby and five static line students – he planned to send them off one by one, then make a 360 climbing turn, and jump on a last run.

At Nimbus, our student rigs were modified B-5 emergency parachutes with 28 foot C9 canopies and double-T (Hustler) steering mod. The opening system was static line with cotton break cords closing the container. A PCA – pilot chute assist system – a short web piece with a male velcro piece attached, was tied to the end of the static line, paired with a piece of female velcro attached to the pilot chute inside the pack.

The static lines were attached to a point of the cabin floor. IKC had a ring in the floor behind the pilot’s seat for the static line hooks – all lines were hooked to the same ring, and all lines were hooked up when loading, one by one. When exiting, the line was stretched out, the break cords broke, the pca pulled the pilot chute out of the slipstream, ensuring a fast opening of the main canopy.

IKC had, like most 206es – a large cargo door at the rear of the cabin on the right hand side, so that students had no wing strut to hold on to, nor any step to use – exiting students had to sit in the door half out, legs dangling, and then push off on the jumpmaster’s order ”Go!”

We took off as normal, climbing to exit altitude 2500 feet. Arne directed me with”left-right”-signs, then placed student number one in the door and ordered ”Go!”. Once the student was away and a normal opening was observed, Arne coiled up the static line (with the pca piece at the end) and shoved it under my seat. New run in, next student, same procedure, in the end there were five static lines stowed under my seat. One last 360 turn and we were at 3500, Arne crouched in the door until we were lined up – gave me a short wave and disappeared. I drew back on the throttle to start the descent.

Suddenly, I hear shouting – and it was not in my headset – but I am alone up here! I look behind me – empty plane – but one of the static lines lies tightly across the floor and out at the rear bottom corner of the door. Suddenly I get a bad feeling, I kick hard right rudder and bank right – and there I see Arne dangling about 15 feet below, hanging by one leg at the end of a static line. I trim the plane. unfasten my seat belt and go behind my seat to see if the static line can be unhooked – but No Way! – it is as taut as a bowstring!

Back in my seat, I call up RY Tower and explain that I have a jumper hanging head down 15 feet under my plane. The air traffic controller (ATC officer Einar Solum) responds with the key words (which I will never forget): What are your intentions?” That started my thought processes – What Now?

It was getting dark (it was the last load of the day), under me I had Rygge’s 2400 metre concrete runway, an 1800 metre parallel runway and 2000 metres of taxiways, to my left I had the large lake Vannsjø, frozen. It was clear to me that I could not land on the concrete surfaces with Arne hanging underneath; he would be killed (in the blinding light of hindsight a landing on the concrete might have worked out). Regardless, I had to land.

But where? The ice on Vannsjø was new and most likely too thin to carry a ton of aircraft – besides; a landing in ice water would create a new problem. My biggest worry initially was about what Arne might do – if the pulled his main or reserve, one of two things would happen: His leg would be pulled off (killing him), or the plane would be stopped in the air and fall down (killing us both). After a while the shouting stopped, and I was relieved – it led me to believe (and hope) that Arne had fainted (he had not – more about that later).

Once again, I was helped by the air traffic controller, who said”What about landing on the grass between the runway and the taxiway?”. Sure, that would be much softer, there was the added padding of the light snow cover, and the landing space was generous. So, I decided: Land between the taxiway and Runway 30 – and land at as low a speed as possible.

IKC happened to be perfectly suited for such an operation: its configuration was ideal, with very large flaps, powerful engine (285 hp), very low weight, as it was empty but for Arne and myself, and the fuel tanks were only a quarter full. I lined up north of the field at 3000 feet, aiming at the landing spot, and commenced a long, long approach, gradually reducing airspeed by increasing flaps, pulling up the nose while adding power ending up about 20 inches MP.

The airspeed crept steadily downward as I approached the landing area, but IKC remained rock stable and the stall warning kept mysteriously quiet. Towards the end, the airspeed indicator was well under stall speed, but the engine kept us flying – like hanging on the prop. Just before touchdown, there was a narrow concrete road crossing over to an instrument hut – when we closed in I reduced power just a little, but IKC reacted like a brick, so I gave it a power burst to get us over the crossing road.

Firm landing! – we are down! I step hard on the brakes and cut the engine, release my seat belt and jump out of the cargo door – and there lies Arne, shouting to me:”I am fine, fine – I’m completely OK!”. I refuse to believe this (I’m thinking maybe a broken back) and tell him: “Lie still, don’t move! – wait for the ambulance!”. ATC had punched the emergency button much earlier, so the ambulance was right there. We hooked off his gear and untied the static line from his leg (the pca had taken a turn around his leg and the male velcro had attached to his jumpsuit leg), put him carefully over on the stretcher, and off to the infirmary with him.

I paced up the aircraft wheel tracks and the trail Arne had made in the snow. The wheel tracks left by IKC measured 35 metres – the drag trail left by Arne was 70 metres – 230 feet – believe it or not. He had dragged 35 metres (115 feet) on the ground while the aircraft was still in the air – braking its speed. Then came the best part: Half an hour later Arne came back from the infirmary – the doctor had found nothing wrong with him, apart from a sore ankle – happy end!

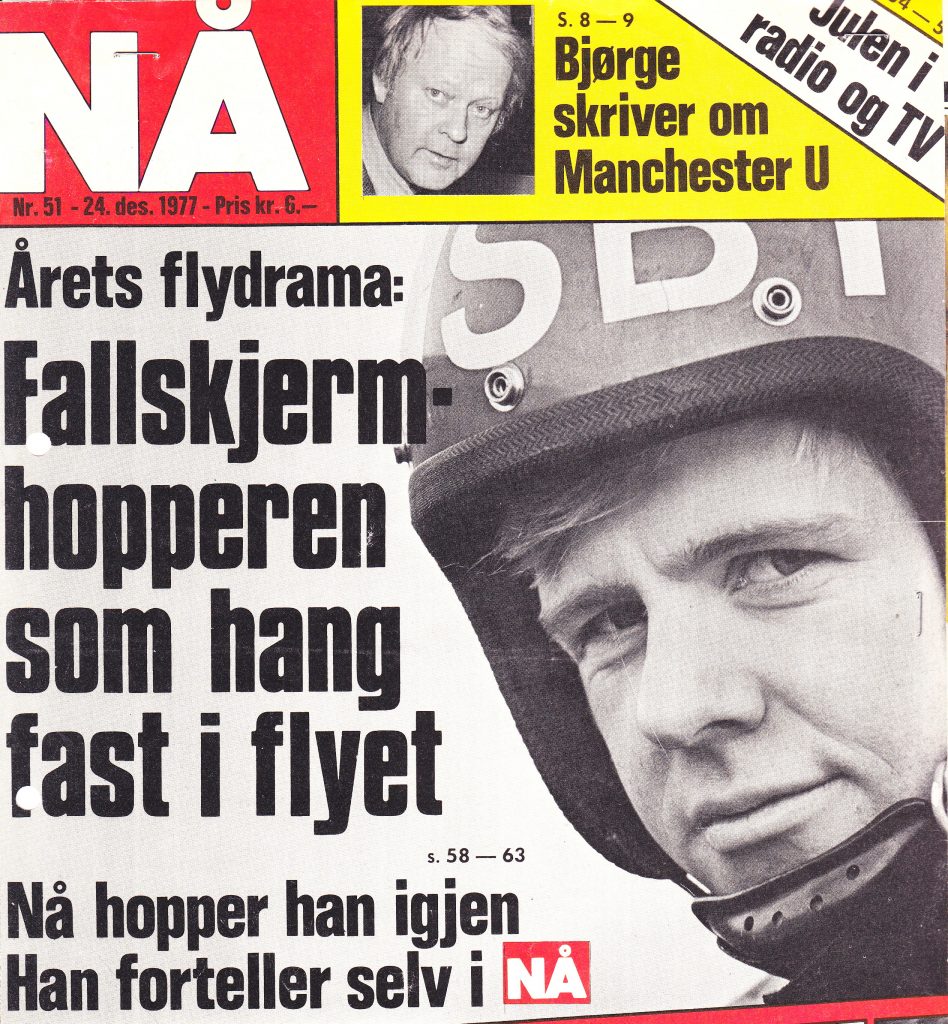

Then, publicity took off – somebody called one of the country’s most notorious news rag, VG. They had an artist draw a picture of the incident (all wrong, with the door on the wrong side of the aircraft) but the sensation was there. The various press agencies picked it up, and the story went world wide as a news item – I received messages and congratulations from near and far, including Australia and the USA. National Enquirer sent a journalist to Oslo to interview me. Then came the pictorial “Nå“ and wanted to do a re-enactment with Arne jumping again, which we arranged with the IKC plus a chase plane and did it again – except for the hanging head down.. The report in Nå! was six full pages.

15 years later, in 1994, the Norwegian TV network TV3 made a program about the incident as part of a series called “Alarmen går”, interviewing both Arne and me, and doing the flying with another 206 owned by Stavanger skydiving club, featuring their skydivers.

Afterthoughts:

There are sides of this story that I have shared only with select people over the years – basically the decision process: Once I had decided to land on the grass, a slow, slow landing was my only objective. I pushed away any thought of what, at that moment, appeared to me as a certainty: Arne would be killed. Behind that lurked another, built in question:

Is my decision the only solution? What happens when I land, having killed Arne, and everybody asks: ”Why didn’t you do that or that i stead, and you would have saved him?” – and that there would be some other, obvious action that would have saved his life, a possibility I had not seen or understood …

As it happened, such a situation did not occur – what I did was right, and everything turned out well – he survived – but the awful feeling of ”what if” still bothers me …

When Arne and I finally got to sit down face to face and talk the whole thing over, Arne tells me calmly: “No, I wasn’t really scared – I kept thinking that it is Eilif who is flying, he has years of experience, knows what he is doing, is steady as a rock, and all will turn out just fine!”

Had he known …