US President Jimmy Carter’s sweeping replacement of strict regulatory regimes with free competition completely reformed large portions of US business life. Additionally, US deregulation has had wide ranging international impact. No mean feat for a one-term US president.

Even if his most important deregulations were initiated, and subsequently completed, by Republican presidents, the fact that they were introduced by a Democrat made them palatable also for the social democrats of Europe, who have since embraced deregulation one after another. A deregulated free market is the political cornerstone of world trade.

Historical Background

Trade and commerce have always been the lifeblood of organised society. Throughout history, both of these activities have been subjected to various forms of control, usually exercised by the sovereign powers of countries or areas. Taxes and duties levied on trade and commerce have been among the governing powers’ main sources of income; they have also proved to be efficient instruments of power.

From about 1700 onward, however, and well into the 1800s, scientific enlightenment opened up for mechanical inventions and the machinery to drive them, while immense new sources of energy were discovered to power it all. The new inventions mechanised manual tasks, creating an industrial revolution, which vastly increased the economic and social importance to civilised society of industry, trade and transportation. This, in turn, forced profound change to the structure of society in the affected countries, transforming them from generally agrarian societies into mainly industrial societies: first in Britain, later in the United States and later again in Western Europe.

In 1776, the breakaway of the American colonies from Britain created a completely new type of civil society, characterised by wide individual and commercial freedom and a reduced role of government – a society that was basically different from its cultural origins in Europe but still embodied parts of the English freedoms and legal heritage. Initially, the independent American industry and commerce evolved with minimal restriction, as it had in England. In Europe in general, governing powers retained control of trade and industry, particularly during the Napoleonic era, leading to strict regulatory regimes and often to direct State participation in industry.

It is a popular misconception, particularly in Europe, that free market economy is a long standing tradition in America. The opposite is the case. The tremendous rate of population expansion and land conquest in the United States in the mid- and late 1800s, especially the advent of new transport modes (railways, riverboats, shipping), created a need for harnessing and regulation to avoid chaos. To establish control and to curb excesses, the US Congress enacted a number of very strict laws controlling interstate commerce and transportation.

As a result, transport, utilities and banking in the United States, while remaining within the domain of private enterprise, became heavily regulated through federal legislation. The basic structure and principles of these regulations remained largely unchanged by the United States well into the 1970s.

The first Federal controls were introduced in 1887 when Congress set up the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) with power to regulate interstate transportation and control railroad prices and competition. With the advent of road transportation, ICC’s powers were expanded in 1935 to regulate also trucking, while a Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) was created in 1938 to control air transport.

In the United States, government control was strictly limited to regulating – no US government has ever operated any form of transport activity except the US Mail. All forms of transportation, communication and utilities in the United States have been, and remain, operated by private, commercial enterprises.

In Europe, socialism and trade unions gradually grew into major forces in society and eventually, in the 1930s, attained government positions. Governments created centrally controlled economies and eventually a plethora of State owned and operated industry, particularly railways, urban transport and utilities such as power and telecom. Essentially, in Europe, all major economic areas became fully unionised and under State control by 1960.

In the US, on the other hand, socialism in its various forms never found fertile ground and never succeeded in gaining power, and the trade union movement never managed to parallel Europe. The US railway unions of 1890-1917 and later AFL-CIO and the Teamsters, established a significant presence in rail and road transport, as did the UAW in the automobile industry, but the major part of American trade and industry remained relatively un-unionised, and all trade, industry and utilities remain firmly in private hands.

Prelude

President Richard Nixon’s first term (1968-72) saw some substantial economic improvements, including the normalisation of relations with communist China. However, the 1973 Middle East war caused the OPEC oil price rises and the consequent energy crisis. The ensuing US stagflation hit the whole Western world as a shock.

In the US, the effects of a rigid regulatory regime that had lasted for nearly 90 years finally became evident. The strict transport regulations regime, combined with strong trade unions, had rendered the transport industry, in particular the railways, unable to cope with the cost increases, and railway companies went into bankruptcy by the dozen.

In August 1974, Republican President Richard Nixon resigned from office as a consequence of the Watergate scandal. He was automatically succeeded by Vice President Gerald Ford, who inherited the “stagflation” from his predecessor, as well as a transport sector in crisis.

Deregulation

Railways

In 1975, President Ford applied deregulation as the medicine to revive the troubled transport trade sectors, and made several legislative moves. Government regulations and agreements with labour unions rendered the railroads of the 1970s unable to individually change the rates they charged shippers and passengers. Their only option was to reduce costs. But cost-cutting was tightly restricted by union agreements, and the railroad companies were driven into bankruptcy – by 1976 nearly a third of U.S. railroads were in or close to bankruptcy.

Stringent regulations and increased competition from truck and barge transportation had caused a financial and physical deterioration of the national rail network. To rejuvenate the rail sector, President Ford had Congress pass the Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act of 1976. This eased regulations on rates, line abandonment, and mergers.

At the 1976 election, Ford ran for the presidency, opposed by Jimmy Carter, a little known Democrat with minimal experience with politics on the national level, a former peanut farmer from a tiny town called Plains. Ford hoped to win, but the fact that he had pardoned Nixon after Watergate proved too much. The election race was very close, but Carter won over Ford with 50 percent of the popular vote to Ford’s 48.

President Carter determined that further action was needed to revive the railway industry, and Congress followed up with the Staggers Rail Act of 1980. The Staggers Act provided the railroads with greater pricing freedom, streamlined merger timetables, expedited the line abandonment process, and allowed confidential contracts with shippers.

During his single term (1976-80) President Carter followed through Ford’s deregulation ideas, applying them to air transport and trucking. Carter not only continued Ford’s work but also pushed for deregulation of several other key sectors of the US economy, particularly banking. It fell on President Reagan, however (who was also a keen promoter of deregulation), to finalise them during 1980-88. Historically, however – and very importantly – it has come to be identified with Jimmy Carter – a Democrat.

Trucking

The trucking industry was brought under the control of the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1935. For nearly 50 years, from 1935 to 1980, it was almost impossible to secure new or expanded authority to transport goods unless no other transporters opposed an application. The ICC held that a certificated trucker who expressed a desire to carry the goods should be given the opportunity to do so – and the new applicant was denied. In effect this stifled competition.

The only practical way to enter the market was by purchasing the rights of an existing trucker. By the seventies a license to carry goods was selling for hundreds of thousands of dollars. In effect ICC regulation reduced competition and made trucking inefficient. In 1975 President Gerald Ford called for reduction of trucking regulation, and appointed to the ICC new commissioners who favoured competition.

President Jimmy Carter followed Ford’s lead by appointing strong deregulatory advocates and supporting legislation to reduce motor carrier regulation. Later, Carter’s initiatives were followed up by Reagan, who enforced the subsequent laws.

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters – the truck drivers’ union – and the American Trucking Association both strongly opposed deregulation and initially headed off efforts to eliminate economic controls. The deregulation supporters were a coalition of shippers, consumer advocates and liberals such as Senator Edward Kennedy, and a series of ICC rulings reduced federal oversight of trucking. Carter had Congress enact the Motor Carrier Act of 1980 (MCA), which limited the ICC’s authority over trucking. Congress reacted by codifying some of the commission changes, so that the reduction of control became only partially effective, but with a liberal ICC, it substantially freed up the industry.

Air Transport

The first major deregulation of Carter’s presidency concerned the airlines. Before the passage of the act, airlines had to receive government approval of routes from the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB), an exceptionally bureaucratic institution that sometimes kept applicants waiting ten years before getting a decision, and rejected many requests. Technological advances like the jet airliners combined with the 1973 economic climate change placed tremendous pressure on the rigid CAB system. Most of the major airlines favoured the system, which virtually guaranteed their profits, but the travelling public did not, and air transport development in the US suffered.

In 1977, Carter appointed Alfred E. Kahn, a professor of economics at Cornell University, to be chairman of the CAB, who would earn the title «father of airline deregulation». He argued that the CAB was in fact inhibiting growth and encouraging inefficient practices. Kahn also argued that removing regulation would bring a new, efficient equilibrium of price, quantity and quality of air service. Long-haul fares would decline, barriers to entry for new airlines would drop, and airlines could effectively deploy different aircraft for different roles. The Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 removed much of the Civil Aeronautics Board’s control over commercial aviation and greatly improved air transport efficiency.

Banking

Another key piece of legislation passed during the Carter presidency was the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act, passed in 1980. It lessened government control on the interest rates for money deposited and saved in banks, so that with higher interest rates, people would be encouraged to save their money.

The Success of Deregulation

Deregulation – the ending of a regulatory regime that had lasted for nearly 90 years – from the 1890s to the 1980s – has worked well in all modes of transport. Both the American Trucking Associations and the major airlines predicted that service would decline and that small communities would find it harder to get any service at all. In fact, service to small communities improved both by air and by road.

Between 1977 and 1982, rates for full truckload truck shipments fell about 25 percent in real, inflation-adjusted terms. “Less-than-truckload” rates fell as much as 40 percent. A survey of shippers indicated that 77 percent of surveyed shippers favoured deregulation of trucking.

The railroad deregulation of 1976 and later President Reagan’s tax revisions of 1981-82 restored the railroads’ financial health. Container cars and other new technologies also helped to transform inefficient railroads into vibrant enterprises. Corporate strategies varied on the road to success, but the railroads’ resurgence and growth has continued.

Deregulation has also made it easier for non-union workers to get jobs in the transport industry. This new competition has sharply eroded the strength of the unions. By 1985, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters – the truck drivers’ union – was organising only 28 percent of the trucking work force, down from around 60 percent in the late seventies.

The number of new trucking firms and new airlines has increased dramatically. By 1990 the total number of licensed trucking carriers exceeded forty thousand, considerably more than double the number authorized in 1980. The ICC had also awarded nationwide authority to about five thousand freight carriers. The value of operating rights granted by the ICC, once worth hundreds of thousands of dollars, is now close to zero.

Energy & Inflation

A second wave of oil price hikes during the Carter administration caused inflation to skyrocket to as much as 12 percent per year. A widening trade deficit also contributed to the inflation. With five laws passed in 1978, collectively known as the National Energy Plan, Carter created a Department of Energy, allotted money for alternative energy research and created tax incentives to encourage domestic oil production and energy conservation.

In March 1979, nuclear power became part of the nation’s energy crisis. Nuclear power made up more than ten percent of the nation’s electricity supply. A partial meltdown at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania released radiation into the environment, alerting the nation to a potential hazard. The protest movement against nuclear power spread, but even if no further nuclear power plants were ordered in the United States, those already in operation continued in operation and most of those under construction at the time eventually went into operation.

Hostage Crisis in Iran

In 1979, after the Shah had been forced to leave the country and Islamic fundamentalists led by Ayatollah Khomeini took control of Iran, militants stormed the US Embassy in Tehran, taking seventy Americans hostage. This triggered the most profound crisis of the Carter presidency. The hostage ordeal lasted for 444 days, until finally a negotiated release of the hostages was secured on 27 January 1981. The affair greatly lowered the public’s opinion of Carter, and resulted in Ronald Reagan winning one of the most crushing presidential election victories in US history: 489 to 49 Electoral votes in the 1980 elections.

Epitaph

President Jimmy Carter’s epitaph has been much tainted by the Iran hostage affair, by his watering down of the US’ intelligence capabilities (which hit him badly in Iran) as well as by the economic situation in the US during his presidency: rising unemployment, high inflation and tripling of oil prices. It is wrong to say hat his economic policies failed – most of his initiatives were right, but took time to take effect, and did not create measurable improvements until after his presidency. All this has, unfortunately, combined to overshadow his most important contribution.

Even if several of his most important deregulation moves were initiated by President Ford – a Republican president – and several more followed up and implemented by Reagan, another Republican – Carter’s sweeping replacement of strict regulatory regimes with free competition completely reformed large portions of US business life.

Perhaps even more important is the fact that these measures have since served as models for most of the Western world. That they were introduced by a Democrat US president made them palatable also for the social democrats of Europe, who have since embraced deregulation one after another. A deregulated free market is the political cornerstone of the European Union.

All in all, the deregulation reforms in the US had, in the end, wide ranging international impact. No mean feat for a one-term US president.

Norway’s follow up

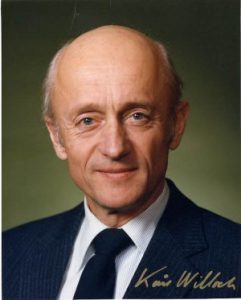

In Norway, the man who broke throgh the mass of Government regulations was Kaare Willoch, who was elected prime minister of Norway in 1981.

He was subsequently succeeded by Gro Harlem Bruntland, who, albeit a social democrat out of Norway’s Lbour party, continued deregulating and privatising the norwegian economy with enthusiasm throughout her two long stints as prime minister – 1986-89 and 1990-96.

All thanks to Jimmy Carter …