As recounted in my previous post in «Life on the High Seas» («Rookie Sailor») I spent the first years of my early youth in the merchant navy – just after WW2. Between age 15 and 19 – from 1946 to 1951 – I served on Norwegian ships. By the 1950s, Norway’s merchant fleet was the World’s fourth largest, crewed by 35,000 seamen – 90% of them Norwegians.

Rookie No More

August 1st 1947 we arrived at Amsterdam from Abadan, and 22 of the crew had given notice and were leaving ship. There was a severe shortage of seamen at that time, so that it was clear that we would be short of crew. In a way, that was good news, since, by law, the actual crew would share the wages of any missing crew members as compensation.

As I recounted in my previous tale (Rookie Sailor), I often scrounged turns at the wheel in my spare time ass mess boy, and had done well, so the captain offered to sign me on as a deck hand – and of course I jumped at that chance. As a bonus, he credited me for my time as mess boy, and signed me on as Youngman (which formally required 12 months as deck boy). I was no longer a rookie.

Woman on board!

Our Sparks (the radio operator – officer by rank) was signing off, and the word spread as wildfire: we were to get a female Sparks! This was about the first female radio operator ever in the Norwegian merchant navy – among 35.000 men and more that 800 male radio operators. When the transport arrived at the quay, 30 men hung over the railing to watch her coming up the gangway. She was a real doll, a 19-year old long haired blonde. Everybody drooled, but the Wise Men aft – Bosun, Chips and the Cook – made it clear to the younger ones who drooled the most: ”Forget it – you need an anchor on your sleeve and a meatball in you cap to have any success there …” . They were proven right.

West Indies

I was put on the 4-8 watch. The transition from a mess boy’s gruelling 80-hour work weeks was like going to paradise. One hour at the wheel, one hour lookout on the foredeck (night-time), another hour at the wheel, another lookout – daytime, the lookout turns were replaced by miscellaneous maintenance work.

With most of the new crew aboard (3 hands short) we went from Amsterdam to Aruba (Dutch West Indies at that time) . Entering the roads of St. Nicholas to anchor and wait for loading space, we all lined the railing to admire the (then) world’s largest tanker – the American 28,000 ton dw turbine tanker ”Ulysses” – that dwarfed our 12,000 tons (the newest “Ulysses” – 2005 – is 300,000 tons dw).

Loading at Aruba was quick, about 18 hours, so shore visits had to be maximised – it became dominated by Cuba Libre – rum and coke – the national drink of the West Indies. This resulted in a large portion of our crew landing in the local (Dutch) jail, where they were put in zoo-like cages. Departure approaching, our First officer sent in a shore patrol, who had to buy out the whole gang and hire a bus to get them aboard. Still, at departure we were only five sober people on deck to cast off, two on the poop, two on the foredeck and me at the wheel. The captain was not amused.

A Wayward Sparks

We spent most of the next half year plying between Abadan in the Gulf and European ports. One of these trips we were returning to Abadan from Bristol, and I was on the 8-12 watch at the time. It was the duty of the last watch turn of the day – the lookout – to wake up the 3rd officer for the coming 12-4 watch. When I went in to wake him up I had to step over to shake him – and there was our lovely Sparks, stark naked – they were both asleep. Up on the bridge later, the 3rd officer came up to me and asked me to keep quiet about it. ”OK,” I said, I’ll keep mum” – which I did. But the Wise Men aft were right …

At the Wheel in the Suez Canal

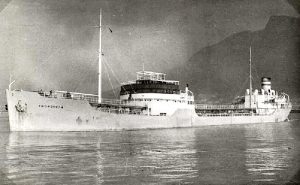

During the trip up fom Abadan in November 1947 the passing through the Suez Canal was to become a very memorable one for me indeed. All ships passing through, both ways, are required to have a Canal Company pilot on board – and the Suez pilots were demanding and choosy. M/T Kollbjørg was fully loaded – 12,000 tons of kerosene, and, on entering the canal’s southern end at Port Tewfik, the captain put me at the wheel.

The pilot looked at me, obviously sceptical, but said nothing, and started out by giving me the courses to steer in points and half-points of compass, not in degrees. The hundreds of books on ships and sailing that I had consumed growing up during the war, a number of them in English, had made me familiar with the points system, so I responded without hesitation in repeating his orders – the pilot soon looked much more satisfied.

When my relief came up to take over after the first hour, the pilot told the captain: ”Keep the helmsman”. That was a right the pilots had, but rarely used – it resulted in my staying at the wheel continuously for five hours, until we tied up at the canal side to let an opposite convoy pass. Those hours remain – to this day – the greatest moment of my life. I had just passed 16 – I didn’t even have hairs on my chest. The captain was all smiles, too.

Trouble in Palestine

Our next trip turned out to be exciting (as well as historical) – we went to Haifa, that time in the British Mandate of Palestine. Israel did not yet exist, but British withdrawal was just around the corner. The Jewish resistance (Haganah) was preparing to take over and establish the new state of Israel, and was harassing the British continuously with bombs and sabotage. Haifa was the terminal of the oil pipeline from Iraq, and very important to the Brits.

Due to the continuous unrest ashore, we were not allowed to leave the ship. While we were anchored in the harbour waiting for a loading space, British warships kept dropping depth charges in the harbour area every 15 minutes to prevent frogmen saboteurs to sink us with limpet charges. ”Kollbjørg” was completely empty, without ballast, and with tank hatches open the ship was like a gigantic bass drum every time a depth charge went off.

Our cargo from Haifa went to Southampton – then another trip to Abadan – it was Christmas before we passed southbound through Suez With a new load of kerosene from Abadan we were ordered to Dublin.

Dublin partying

Our stay i Dublin became quite an experience. I owned a small book of English song texts, and had learned some by heart, among them the Irish folk song Molly Malone. Irish pubs were never known for their reserve, neither for low noise levels, and as soon as the locals found that I could sing Molly Malone – all of it – I no longer had to pay for my drinks. The same happened the next night at a new pub up the street – I must have sung Molly Malone a hundred times those two nights. I believe that it is the only time my voice has brought me benefits.

Going home

The rest of the winter and spring we went up and down between Abadan and North European ports, until we ended up in Hull and loaded a lot of pipes on deck: future steam coils in the tanks in order to convert to crude oil transport – then on to Antwerp. When we turned into June, I had been aboard for 19 months, and had 1500 kroner ($ 300) in a bank in Oslo. On June 25th, four of us signed off at the Norwegian consulate in Antwerp. The captain provided me with an extra bonus: He certified that I had served 19 months as a deck hand – that would be enough for me to sign on as OS (Ordinary Seaman – lettmatros) next time around.

We paid for a four-berth cheap passenger cabin on the ”Brabant”, a Fred Olsen passenger ship plying between Antwerp and Oslo – it was strange for us to be passengers for a change. (In a twist of fate, this happened to be the very same ship that brought my family and me the same stretch 12 years earlier, when we were passing through as refugees from the Spanish civil war).

Four days later we landed in Oslo, ad I took the train to Fredrikstad – I had wired ahead, so they were prepared. What my Mother was not prepared for was that I was 3 inches taller and 30 pounds heavier than when I left i November 1946 – no fat, all muscles – when I rang the bell at our home that day, it took some time before she recognised me .